7 principles to guide your prototyping

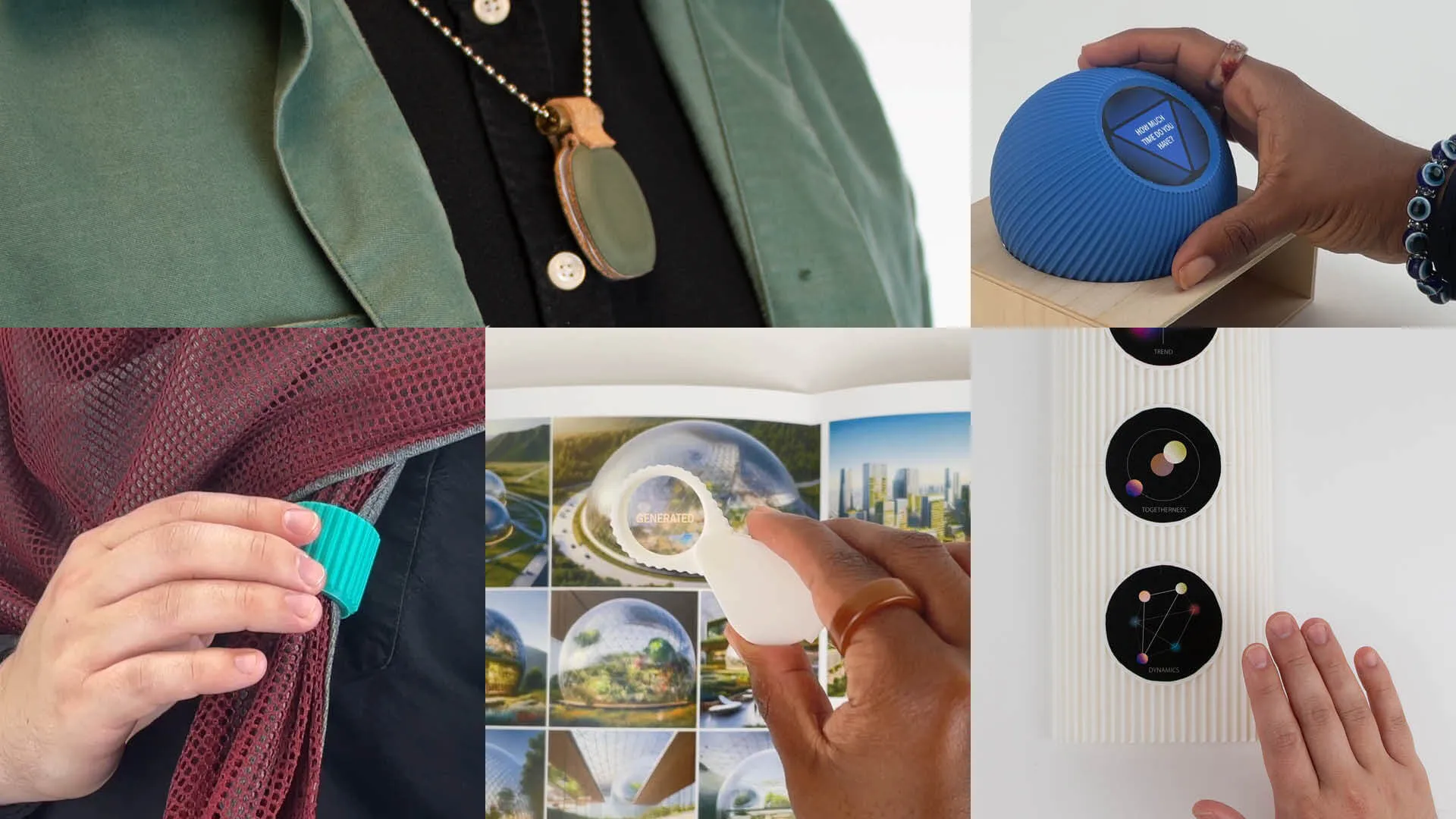

A few years ago, we partnered with Google and Levi’s to build the mechanics inside the Jacquard jacket, which allows wearers to control their smartphones with a brush of their sleeves.

Originally designed for cyclists, the idea was that we could give them access to information from their phones while reducing distraction. As we worked to progressively learn how the electronics and denim could work together as one seamless product, we explored hundreds of variations of the smart tag, failing our way toward the best version. From 3D-printed shapes to sewn straps and overmolded silicone assemblies, each iteration brought us one step closer to an ultimately successful product launch.

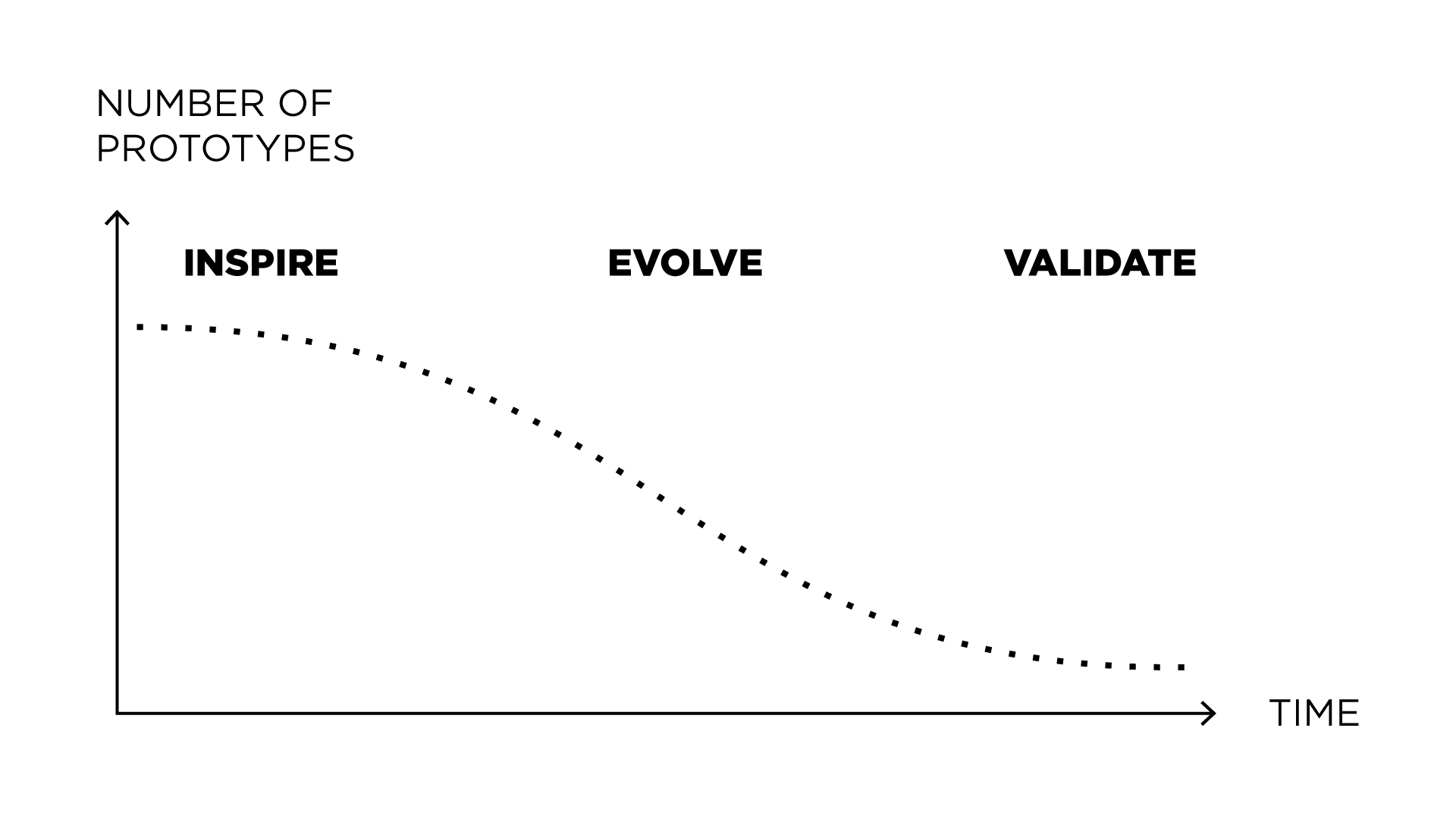

At IDEO, we’re big believers in the idea that if you want to succeed sooner, you’re going to have to fail earlier. And fail a lot. But each time you build something, you learn something new about the challenge you are trying to solve. This iterative cycle of question, make, answer, and ask a new question is why prototyping is such an important part of the design process. The more you make, the more—and the faster—you learn. And ultimately, the better the end product. That’s why we always encourage our teams to make something—early, often, and repeatedly.

Here are seven principles that help guide our prototyping process, as we fail our way to the best version of whatever we’re making.

Early prototypes should be rough, rapid, and right

When you are working at a lower fidelity, you spend less time and fewer resources on each iteration, so you can build more and learn more. The key is to know what questions you’re trying to ask—and answer—with each new variation. What can you make to address those questions first? What is the fastest way to make something you can test? Keep those goals in mind to guide your process.

On a project developing a new laryngoscope (a device that helps doctors examine the larynx), we needed to quickly explore many ways a retraction mechanism might work, and what the implications each option would have on the device’s internal architecture. We prototyped at just enough fidelity to convince ourselves and our client that the task was possible, and to align on the leading methods we had for achieving it.

Add refinement only when and where you need it

Every time a prototype helps you answer a question, you take a step toward a higher-fidelity design. In this progression, the prototypes usually start to get more complex—as do the methods for making them. Improvements and iterations start to take more time as complexity grows, so prioritize your efforts accordingly. Keep asking yourself, “What do I want to learn from this prototype, specifically?”

On a fairly recent project, one of our teams was designing a new handheld massage device that incorporated a digital touchscreen. Even though it was a big part of the final product, we consciously chose to keep that complex element out of our prototypes for months, because we hoped to evaluate ergonomics, size, and use patterns before digital interactions. We added functional digital elements once we felt we needed feedback to keep evolving and testing the concept.

Embrace pivots

When you are building early, low-fidelity prototypes, try to keep all the possible doors open and maximize exploration. We like to work with modular elements, and avoid permanently removing or attaching things. That way you can quickly change directions or incorporate new ideas without having to start from scratch. It’s a practical way to save time and money, and to keep yourself from locking in on one idea.

Embracing pivots was key to our success when we were designing a new set of multi-tool experiences for SOG, a specialty knife and tool manufacturer. A multi-tool can do so many things, but each form factor lends itself to being particularly good at just a few core tasks. By prototyping in a way that allowed us to mix and match functions across form factors, we were able to easily pivot and experiment with various tool elements across the product line without over committing to a specific direction too soon.

Don’t reinvent the wheel

You could fabricate bespoke elements for each prototype you’re building—or you could take advantage of what's already out there, using existing products as a foundation. No point in wasting time building something you could easily grab from elsewhere. The spirit of prototyping is all about speed of execution, so it’s always better to focus on what you want to learn without getting bogged down solving additional problems. Plus, taking things apart is in itself a way to learn—and it’s fun!

When we developed a scent-ring-blowing robot with the furniture company Moooi, we turned to all sorts of other products as we figured out the best way to create visible scent rings. We landed on a viable solution sooner because we started from existing product architectures—like solenoid valves (electrically -controlled valves used to allow or prevent the flow of media) and speakers.

Always be documenting

If every prototype is a question, and every interaction with a prototype provides an answer, you need to capture those answers as best you can. Plus, when you’re working at low fidelity, things can break, fall apart, or even disappear. It can be easy to forget to set up a phone and hit record, but don’t make that mistake. Short videos and still images are amazing tools for telling the story behind a prototype—why you made it, what you hoped to learn, what users' reactions were, and ultimately how the prototype pushed your design forward.

No one wants to get the message, “Hey I think I just broke the prototype.” But it happens to all of us, and having documentation can be a lifesaver. When our team was creating a folding infant travel bassinet for an IDEO PlayLab client, a delicate, 3D-printed collapsing mechanism was broken just hours before we needed to ship our functional model to the client. Luckily, sending them a video of the mechanism in action created the extra time we needed to print new parts and fix the model—just in the nick of time.

Don’t forget your prototype is … just a prototype

All prototypes are meant to be learning tools that elicit feedback, and the point of prototyping is to discover new challenges, problems, and flaws as you progress to the right solution. Sometimes that means you’ll hear critical things about a prototype you may have spent hours working on—and eventually you’ll probably have to provide feedback for others, too. Prototyping isn’t about defending your perfect creation; it’s about amplifying the speed at which you can learn to enable you to get to the right solution.

Often, IDEO will send research participants several prototypes for evaluation. One of the first things we tell people is, “It's okay if you break the prototype,” because we know it frequently happens. It's more important to allow for genuine interactions and feedback than it is to be overly precious with our models.

This might seem like a lot of information, but these principles are simply guidelines—there’s no right or wrong way to prototype. We think of it as a dance between questions and answers, constantly taking steps toward a more resolved and robust design. That’s why the last principle is, don’t forget to have fun! Rolling up your sleeves and making something is one of the most rewarding parts of the design process, and one of the critically important ingredients in IDEO’s approach to solving hard problems with our clients.

Getting stuck in your own prototyping process? Get in touch so that we can work together to figure it out.

Words and art

Subscribe

.svg)